Yesterday, according to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum twitter feed, was the 99th anniversary of the day Robert Goddard filed his first patent for a ‘rocket apparatus’. I really hadn’t known that. As with many of their ‘This Day in History’ tweets – TDIH for short – it is the little details that are the most fun.

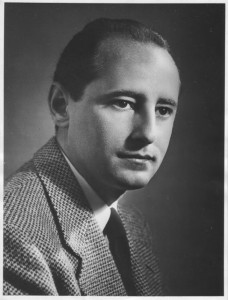

Goddard is plainly an important figure – a pioneer of early rocketry, and the first to experiment with liquid propulsion. His meticulous paper on ‘A method of reaching extreme altitudes’, published by the Smithsonian Institute in 1919, earned him longstanding public ridicule from which he never really recovered.

At least Goddard would prove his critics wrong in the end. And he now has a lunar crater named in his honour as well, of course, as NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre. But let’s face it, he never got anywhere near space flight. His first liquid fuelled rocket reached 41 feet, landing in a nearby cabbage patch. Though he had some greater success with later experiments, none of them approached anything like ‘extreme altitudes’ – at least by his own definition.

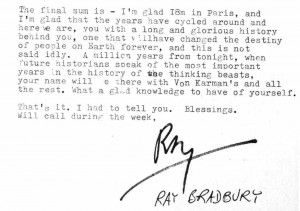

Nor did he provide any theoretical foundation for modern astronautics. Theodore von Kármán’s judgement was pretty harsh but, as far as I can see, it is entirely accurate: ‘there is no direct line from Goddard to present day rocketry’, recalled von Kármán in his memoir – ‘he is on a branch that died’.

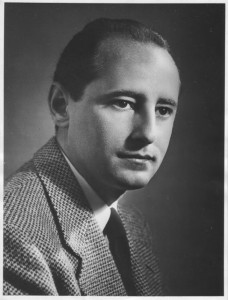

Sometime in 1937, von Kármán and Goddard’s patron Harry Guggenheim tried to encourage Goddard to collaborate with a young Caltech PhD student called Frank J. Malina. The reclusive Goddard was having none of it, and Malina – together with his colleagues in ‘the Suicide Squad’ – followed a very different engineering path.

Where Goddard favoured obsessive secrecy, Malina believed in collaboration and scientific dissemination. Goddard filed patents and got nowhere. Malina and his fellow Caltech researchers openly published their work, encouraged teamwork and made astonishing progress.

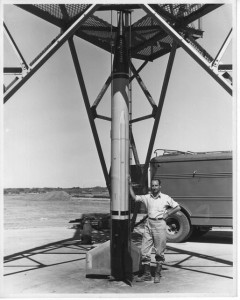

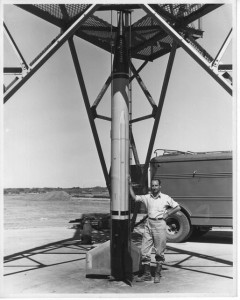

One month after Goddard’s death, and just a few miles away across the desert, Malina and his team made the first successful flight of their rocket, the WAC Corporal. It reached 45 miles.

Should we know about this? Yes.

This was America’s first successful high altitude rocket, that is to say, it could travel higher than balloon technology at the time – important if you wanted to study the upper atmosphere.

It was also the world’s first successful sounding rocket. Admittedly, Wernher von Braun’s V-2 preceded the WAC Corporal but then the V-2 wasn’t designed as a research vehicle – its aim was to terrorise civilians. (Von Braun was born a few months before Malina. His recent centenary was hard to miss.)

In 1949, the WAC Corporal was placed on top of a V-2, to become the second stage of the world’s first viable staged rocket – the BUMPER WAC Corporal. On 24th February 1949, it reached the incredible altitude of 244 miles becoming the first human object to reach into extra-terrestrial space – eight years before Sputnik.

Later the WAC Corporal was refined and weaponised as the Corporal – the first rocket authorized to carry a nuclear warhead. It became, in other words, the progenitor of contemporary weapons of mass destruction.

America’s first successful rocket brings with it a mixed heritage, though one common to the later history of astronautics – caught, as it is, between the transcendent ideals of exploration on the one hand, and the hard-nosed architects of death on the other.

But, still, it seems impossible to ignore this astonishing success and the engineering genius of its chief designer, Frank Malina.

Does Malina have other claims to recognition from America’s space establishment? Only that, along with von Kármán, he founded NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. And Aerojet.

Today is the hundredth anniversary of Frank Malina’s birth. So how is this being commemorated at JPL, the institution he founded? I don’t know. There is nothing on their website or, thus far, on their twitter feed. Maybe they have plans, as yet unannounced, to give commemorate him with a small piece of Martian topography. This would be welcome but a little surprising.

I still hope that the NASA History Office may yet mark the occasion. An earlier tweet, however, was not encouraging: “today is singer-songwriter Sting’s birthday who produced the song “Walking on the Moon”.

No matter. I join with those who admire Frank Malina’s extraordinary achievements: in rocketry, in kinetic art, in international scientific cooperation and in arts-science dialogue (for which purpose he founded the journal Leonardo). With them, I raise a glass to his memory.

The built environment might have been equally striking had countless images of this abandoned village not already been intimately known to me since childhood.

The built environment might have been equally striking had countless images of this abandoned village not already been intimately known to me since childhood.